Last month The Vessel opened in Manhattan, New York. It consists of a set of 154 staircases arranged in a cylindrical, honeycomb-like shape. Its creators, “think of [it] as a three-dimensional public space, like a park, but taller.” (Schwab) The structure garnered widespread criticism with critic Kate Wagner suggesting that it represents, “an architectural practice that puts the commodifiable image above all else, including the social good, aesthetic expression, and meaningful public space.” (Wagner) This interest in “commodifiable image” is clear in the Vessel’s terms and conditions which stipulate that creating any media including The Vessel gives the company rights “to use my name, likeness, voice, and all other aspects of my persona for the purpose of...promoting, advertising, and improving the Vessel” (Yakas) This sinister legal underpinning is a harbinger of a new conception of public space—one that is focused on the image and social media friendliness of the space rather than interest in the physical space itself. This new paradigm suggests that the mediation of one's experience in public space through technology—specifically as enabled by smartphones—has triggered a change in the purpose, social possibilities, and norms of that space.

In order to consider the changes that are occurring in public spaces due to this technology, one must first understand previous theories of that space’s sociological function. There are two pieces to consider; the immediate, local interactions between individuals and the macroscopic conceptual and sociological results they bring. In consideration of the former, Stéphane Tonnelat writes “public spaces are the realm of unfocussed interactions between anonymous strangers. The chief rule is one of ‘civil inattention,’ which helps people grant one another the right to be present and go about their own business.” She explains that strangers must cooperate to enact this rule, for example, by navigating crowds politely and by exhibiting “ ‘restrained helpfulness’, such as giving the time or directions.” (Tonnelat 5) This is a description of public space that most of us are familiar with. One in which a person feels safe and possibly even anonymous, while still supporting the possibility of sociability.

This immediate form of public sociability has been drastically affected by modern mobile technologies. Unfortunately, though, the public perception of this change is generally negative. A common complaint by those who did not grow up in the smartphone era is that this new digital space is taking young people out of the physical world that they should be completely immersed in. Truch and Hulme articulate this concern, writing, “Communication is now increasingly abstracted from the physical location of two individuals. This has resulted in individuals being increasingly engaged in the ‘phonespace’ and therefore having to manage simultaneous existence and self-presentation in two spaces. This can cause stress for both the individual and for those around them.” (Truch and Hulme 6) While the idea of stress being caused by an increased pressure to juggle multiple “social identities” has some merit, I would argue that it is not a new phenomenon. Especially in the rise of urban living following industrialization, people have been pressured to keep up several personal, professional and familial personas perhaps all within the same day. Hatuka and Toch further address this accusation writing, “...people do not use technologies to ‘withdraw’ from public space (De Souza e Silva and Frith, 2012: 36). Rather, they use mobile technologies to...interface their relationships with the other people and the space around them (De Souza e Silva and Frith, 2012: 27).” This suggests a different way of viewing the interaction of digital and physical space—as one that gives more control to the individual. The young of today are not being unwillingly dragged from the world by the lure of their smartphones, they are navigating new ways to filter their interactions in physical spaces using the digital.

Further focusing on the effects of location-based mobile technology on public spaces Hatuka and Toch suggest that smartphones can allow people to mediate their experiences writing that they allow, “the individual to participate simultaneously in multiple spheres of action and communication...Above all, they allow the individual to create elastic boundaries between the public and private and between the personal and the collective, modifying the ritual dimension of human communications in place.” (2203) Here, the authors are suggesting that these technologies augment one's ability to interact with public space. The multiple dimensions of engagement allow members of the public a higher degree of control over their personal and communal space, as well as their ability to communicate with others. They recognize the unique ability mobile technologies have to empower this reshaping of public space. They write that societies “can develop technology as an instrument as well as a socio-spatial tool, a juxtaposed site of the virtual and the material, that supports publicness.” The development of this technology as a meshing of “virtual and the material”, as a tool to foster intersections between digital and physical public space is what will enable this iteration of technology to truly disrupt the previously described conception of the public space.

Beyond just mobile technology as a sociological filter, I would argue that it is a tool that truly augments public social interactions. Location-based platforms allow users to express themselves, not only to previous contacts but sometimes to strangers. This projection of oneself, perhaps in the form of a Tinder profile or a gaming avatar functions as an addition to public presentation in physical space. The person sitting across from you on the subway might not be identified only by their appearance or immediate real-world actions but through profiles and digital actions. This is part of the reason why previous generations have been so quick to dismiss the influence of smartphones and their location-based platforms. The positive aspect of young people’s engagement with these technologies is completely hidden to those not participating with it. What may look and feel like a situation full of possibility to a digitally active person can appear to be antisocial and alienating to others on the “outside.” While this distinction between insiders and may seem unfortunate (and may, in fact, discriminate against underprivileged and minority individuals in light of the “tech gap”), it is a crucial mark of an impactful social tool. The existence of outsiders confirms the existence of the group itself. Thus, these platforms are not only allowing savvy users to mediate their experience of public spaces, but to augment them and to create novel digital interactive places.

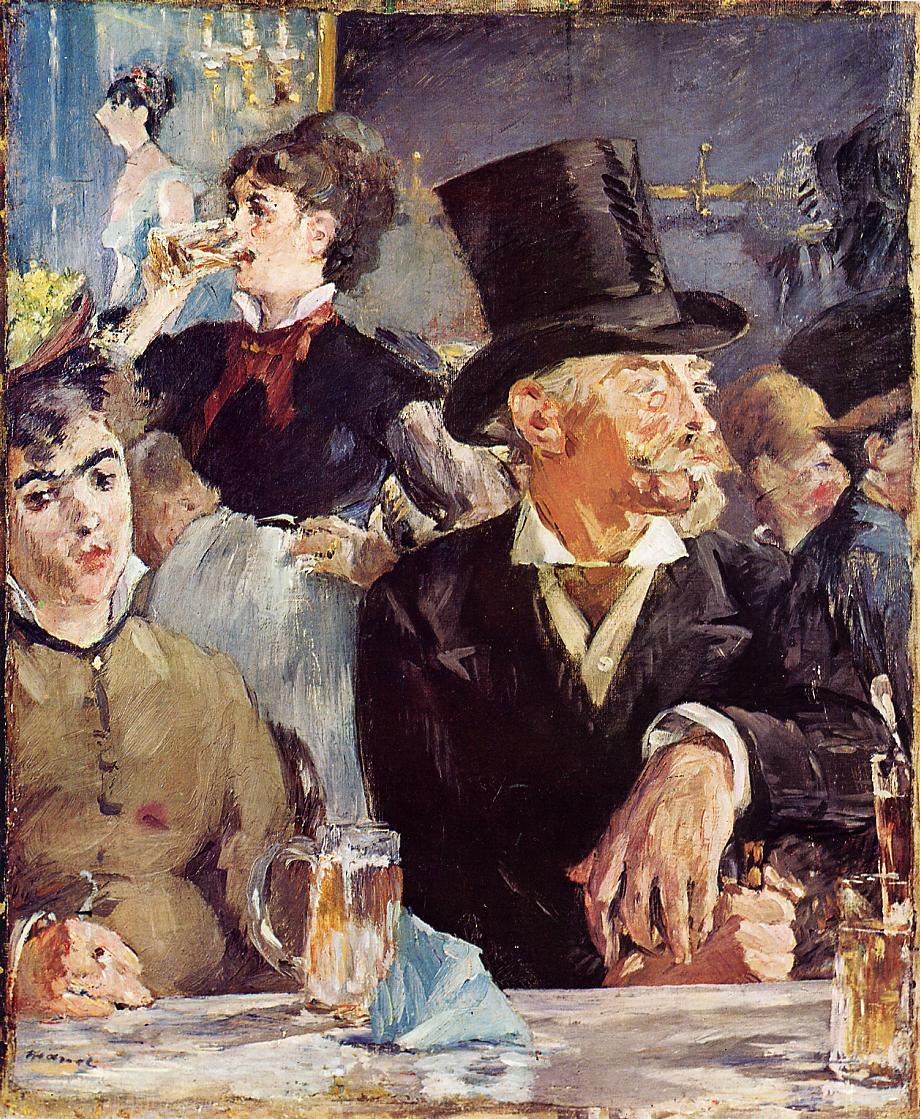

In addition to the consideration of this immediate, physical type of change in sociological public spaces, one must examine the macroscopic effects. In The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, Habermas traces the formation and transformation of “the sphere of private people come together as a public.” This sphere was an important sociological institution which allowed for checking of state and church power and disruption of stagnant social order. Particularly, Habermas identifies the rise of salons and cafés in Western Europe as primary drivers in the formation of this new public. He writes, “they all organized discussion among private people that tended to be ongoing;...they preserved a kind of social intercourse that...disregarded status altogether…discussion within such a public presupposed the problematization of areas that until then had not been questioned…[the culture] established the public as in principle inclusive.” (Habermas 36) These physically and ideologically divergent spaces allowed for the formation of the public sphere, by causing a societal fragmentation from the previously very unified church and state. Eventually, the features of twentieth-century mass media replaced these spaces and deeply damaged this new public through a type of reunification of ideas. Habermas writes “The world fashioned by the mass media is a public sphere in appearance only.” (171) and that with mass media, “Publicity loses its critical function in favor of a staged display.” (206) Again this argument highlights the idea that fragmentation is required in order for the public sphere to thrive. When mass media come to replace these spaces and reunify them, the public sphere disappears.

With this background, the prospect of new public spaces shaped by mobile technologies becomes especially exciting. Just like the cafés functioned as the physical environs for the formations of new types of public, so too can the spaces created by these technologies. The meshing of digital and physical space creates an entirely new type of place—one full of the promise of social fragmentation that the cafés and similar venues held for Habermas. This space exhibits constructive social fragmentation most clearly in its support for partial anonymity and its ability to reshape the meaning of actions in physical space.

There are three important platforms to highlight in terms of their ability to provide anonymity and corresponding social fragmentation. The first and most anonymous would be a platform such as YikYak. Functioning as a localized message board, this app embraced complete anonymity. This resulted in it functioning as a gossip board for many high schools and universities. Its value consists of little more than entertainment. Trending a bit away from complete loss of identity is Tinder. Showing only a user’s first name to potential matches and allowing users to choose their own photographs and personally identifying information, the app gives users just enough identity to make a first impression on potential matches, yet not enough to facilitate harassment that is common on dating apps. The last, but perhaps most interesting application of anonymity in location-based apps is found in Pokemon Go, a location-enabled, augmented reality game. The app shows its users on a map which allows each player to know that others are playing around them but gives no other personally identifying information. This allows for a type of positive digital space mediation in which players are able to make contact with others in physical space who they suspect are players, and those others can choose to reveal their identifying information.

It is clear that different applications of anonymity in these location-based services promote different types of behaviors. Full anonymity can promote free expression but is typically unhelpful in actual societal change and progress—hence Yik Yak’s ultimate demise as a breeding ground for hostility. Partial anonymity can be a much more useful tool in the development of these services in that they can help users to be more open—as in Tinder—or more sociable—as in Pokemon Go. This connects back to the fragmentation of social space. The partial removal of identifying information as well as the importance of physical space is key in this. Instead of playing games without any possibility of real-life contact, or using a dating app that only supports the possibility of a small number of one on one meetings, these platforms create new spaces that overlap the physical and allow a potentially productive divergent, purpose-driven space.

Another interesting development in the design of these platforms is gamification. In an analysis of the gamification of the popular restaurant rating app FourSquare, Firth writes, “location-aware mobile technologies can become a lens through which individuals “read” their surrounding space…A local bar can be read as a prize to be won...My data show that Foursquare can render the everyday world legible in new ways, primarily by rendering physical locations as digital objects to be collected and competed over.” A similar phenomenon was seen in Pokemon Go, which rewarded users for walking and exploring new digital and physical places. This ability that mobile technology allows revealing new readings of the world can be exploited to create spaces in public that support the kind of fragmentation that is needed by the public sphere. Gamification can create new boundaries that exist as the walls of the cafés, splitting up physical space into meaningful bunches bringing the public sphere truly out in public.

Perhaps a less hopeful aspect to consider in this new formation of public space is the influence of capitalism. Just as in the cafés described by Habermas were privately owned places, so too are the location-based services discussed. Though most are free to use, they nearly universally take advantage of the vast datasets generated by user’s activities order to make money. Surely, the services they provide are invaluable to users. It’s hard to imagine local news being a good alternative to Google map’s hyper-accurate crowd-sourced traffic data or manually calling a taxi service rather than just getting an Uber. However, at the end of the day, the company is more interested in its bottom line than humanitarian concern for its users or any concept of the public sphere. Though the cafés were still able to foster the growth of controversial discourse, there is a large concern that these new digital public spaces may not. Controversial conversations thrived in the cafés because the owners were incentivized to sell coffee and tea much more than to surveil and censure conversations had by patrons. Additionally, such surveillance and censorship would have been quite difficult—a single human barista can only keep track of a limited number of conversations at a time. This is simply not the case for many location-based platforms today. It is easy to imagine an app like Yik Yak being more interested in not being banned at a location than in supporting truly free speech. Additionally, these platforms have powerful tools to support detailed and precise censorship in ways that authoritarian regimes couldn’t have even imagined just a few decades ago.

The space found at the intersection of digital and physical is very new and potentially very powerful. On an immediate physical level, this space gives users new tools to mediate their social interactions with strangers. It also allows users to augment these interactions and express themselves in deep, multifaceted ways. These spaces also are enabling a refragmation of the public sphere, just as in Habermas’ descriptions of the café. This could lead to widespread changes in the functioning of public discourse and democratic participation. However, one must be mindful of the potential downfalls of this new public. Corporations such as that which runs The Vessel may be able to convert the attention of this new public into capital—but it can just as easily generate criticism of the predatory capitalism it represents. The hope going forward is that this new type of space can continue to support and encourage such discourse and start opening up even more novel public spaces for citizens to participate in.

Works Cited

Habermas, Jurgen, Jürgen Habermas, and Thomas Mccarthy. The structural transformation of the

public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society. MIT press, 1991.

Hatuka, Tali, and Eran Toch. "The emergence of portable private-personal territory:

Smartphones, social conduct and public spaces." Urban Studies 53.10 (2016): 2192-2208.

Schwab, Katharine. “Why Everyone Hates the Vessel.” Fast Company, Fast Company, 29 Mar.

2019, www.fastcompany.com/90326416/why-everyone-hates-the-vessel.

Tonnelat, Stéphane. "The sociology of urban public spaces." Territorial evolution and planning

solution: experiences from China and France (2010): 84-92.

Truch, Anna, and Michael Hulme. "Exploring the implications for social identity of the new

sociology of the mobile phone." global and the local in mobile communications: places, images, people and connections’ conference, Budapest. 2004.

Wagner, Kate. “Fuck The Vessel.” The Baffler, 28 Mar. 2019,

thebaffler.com/latest/fuck-the-vessel-wagner.

Yakas, Ben. “PSA: The Hudson Yards 'Vessel' Has The Right To Use All The Photos & Videos

You Take Of It Forever.” Gothamist, 18 Mar. 2019, gothamist.com/2019/03/18/psa_the_vessel_claims_it_owns_all_your_photos.php.